The following was originally published on the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII).

This article details how to construct an unlevered discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis for Nike Inc. (NKE) by using finbox.io’s five-year valuation model. Note that unlevered free cash flow refers to the cash a business generates before paying any providers of capital such as debt and equity holders.

The basic philosophy behind a DCF analysis is that the intrinsic value of a company is equal to the future cash flows of that company, discounted back to present value. The general formula is provided to the right. The intrinsic value is considered the actual value or “true value” of an asset based on an individual’s underlying expectations and assumptions.

Cash flows into the firm in the form of revenue as the company sells its products and services, and cash flows out as it pays its cash operating expenses such as salaries or taxes (taxes are part of the definition for cash operating expenses for purposes of defining free cash flow, even though taxes aren’t generally considered a part of operating income). With the leftover cash, the firm will make short-term net investments in working capital (an example would be inventory and receivables) and longer-term investments in property, plant and equipment. The cash that remains is available to pay out to the firm’s investors: bondholders and common shareholders.

I will take you through my own expectations for Nike as well as explain how I arrived at certain assumptions. The full analysis that was completed on January 26th, 2017, can be viewed in this Google sheet. An updated analysis using real-time data can be viewed in your web browser. The steps involved in the valuation are:

1. Forecast Free Cash Flows

- Create a revenue forecast

- Forecast EBITDA profit margin

- Forecast depreciation & amortization expenses

- Select a pro-forma tax rate

- Plan/estimate capital expenditures

- Forecast net working capital investment

- Calculate free cash flow

3. Estimate a terminal value

4. Calculate the equity value

Step 1: Forecast Free Cash Flows

The key assumptions that have the greatest impact on cash flow projections are typically related to growth, profit margin and investments in the business. The analysis starts at the top of the income statement by creating a forecast for revenue and then works its way down to net operating profit after tax (NOPAT), as shown below.

From NOPAT, deduct cash outflows like capital expenditures and investments in net working capital and add back non-cash expenses from the income statement such as depreciation and amortization to calculate the unlevered free cash flow forecast (shown below).

Capital expenditures or fixed capital investment does not appear on the income statement, but it does represent cash leaving the firm, which is why it is subtracted from NOPAT to reach free cash flow. Capital expenditures used in the DCF model represent a net amount, meaning the figure is calculated by subtracting proceeds from sales of long-term assets from capital expenditures. It is the change in capital expenditures that matters for this model.

Working capital is often used as a measure of a company’s efficiency and short-term financial health. It is generally calculated as current assets minus current liabilities.

Working capital investment, or net working capital, in the DCF model is equal to the change in working capital, excluding cash, cash equivalents, notes payable, and the current portion of long-term debt. It’s important to note that one would add the change in working capital to NOPAT if there was reduction in working capital over the period. It would be added back because it represents a cash inflow. This concept is confusing to many. An increase in working capital implies that more cash is invested in working capital and thus reduces cash flow. Firms with significant working capital requirements will find that their working capital grows as they do, and this working capital growth will reduce their cash flows. It is more common to see a cash outflow for the change in net working capital.

Non-cash charges are added back to NOPAT to arrive at free cash flow because they represent accounting losses required to be reported on the income statement but they didn’t actually result in an outflow of cash. The most significant recurring non-cash charges are typically depreciation and amortization. But other non-cash charges or expenses that are typically non-recurring in nature could include:

- Amortization of intangibles,

- Goodwill impairment,

- Asset write-down,

- Provisions for restructuring charges and other non-cash losses (these expected losses should reduce future free cash flow accordingly in the model’s estimates),

- Income from restructuring charge reversals and other non-cash gains,

- Amortization of a bond discount (add back to net income to calculate free cash flow),

- Accretion of a bond premium (subtract from net income to calculate free cash flow),

- Deferred taxes (if you expect that deferred taxes will continue to increase in the future),

- Acquisition expenses representing the costs involved in acquiring a business or a customer (can be cash or non-cash expenses), and

- Litigation expenses relating to legal matters such as settlements and patents.

Finbox.io’s valuation models retroactively adjust historical financials to exclude these non-recurring items. We exclude these items to gain a better sense of how the company has performed in its normal course of business and since they are typically non-recurring charges, their exclusion helps provide a “cleaner” picture for comparing historical performance to projected performance.

Create a revenue forecast

When available, the finbox.io’s pre-built models use analyst forecasts (data from Zacks Investment Research) as the starting assumptions. To forecast revenue, analysts gather data about the company, its customers and the state of the industry. I typically review the analysts’ forecast and modify the growth rates based on historical performance, news and other insights gathered from competitors. Note that if a company only has a small number of analysts giving projections, the consensus forecast tends to not be as reliable as companies that have several analysts’ estimates. Another check for reliability is to analyze the range of estimates. If the range is really wide, it may be less accurate.

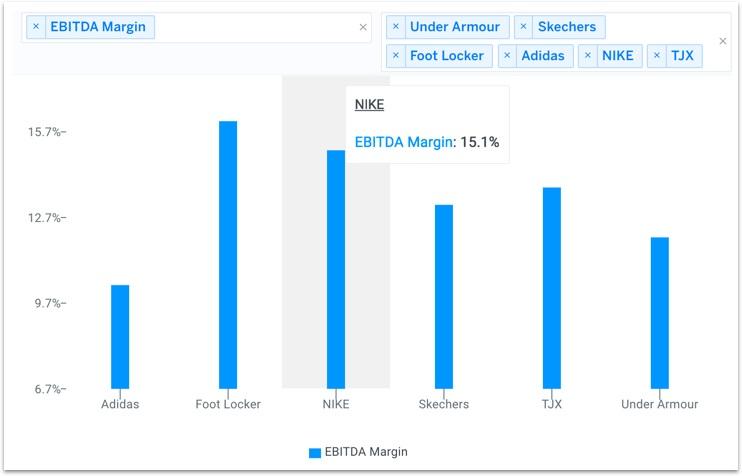

The charts above and below compare Nike’s historical and projected revenue growth to a group of comparable companies that I selected: Adidas (ADDYY), Foot Locker (FL), Skechers (SKX), The TJX Companies (TJX) and Under Armour (UA).

The company’s five-year compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10% trails only Under Armour’s, which has a five-year CAGR of 27%. However, Wall Street expects Nike’s top line to grow at 8.6% annually over the next five years, which is most comparable to Adidas and Skechers.

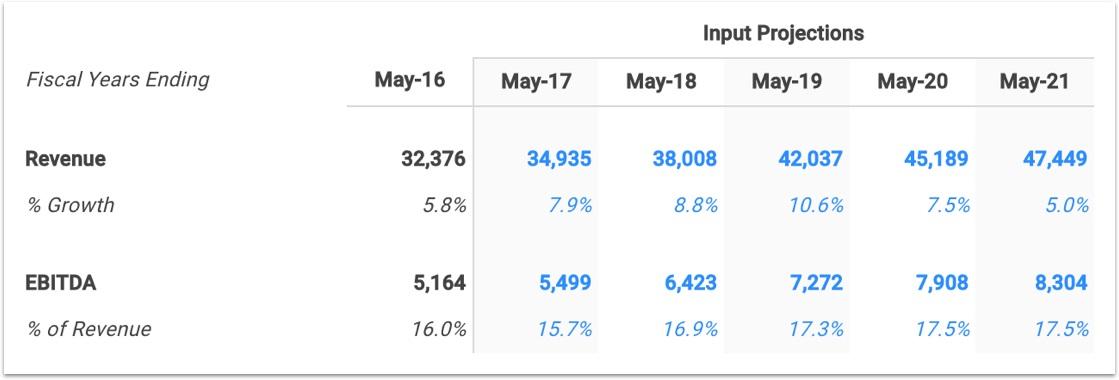

In my model, I conservatively adjusted the growth figures in the final two years so that revenue growth equals 5% in fiscal year 2021. I brought down Wall Street’s rosy outlook in 2020 because (a) it seems unreasonable based on Nike’s recent growth trends over the last five years and (b) there are reports that the company’s market share is declining in face of increasing competition. My 5% revenue growth selection in the terminal year is below the majority of the peer companies’ projected performance, which supports the declining market share assumption. Reading through investor presentations, earnings announcements and other SEC filings helped me get comfortable with my revenue forecast, which is shown below.

Forecast EBITDA Profit Margin

The next step is to forecast the company’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). Note that EBITDA is a commonly used metric in valuation models because it provides a cleaner picture of overall profitability, especially when benchmarking against comparable companies. This is because it ignores non-operating costs that can be affected by certain items such as a company’s financing decisions or political jurisdictions. For more detail, see this EBITDA definition.

EBITDA margin is calculated by dividing EBITDA by revenue. The higher the EBITDA margin, the smaller the firm’s operating expenses are in relation to its revenue, which may ultimately lead to higher profit. Lower operating expenses for a given level of revenue can be a sign of internal economies of scale.

The charts below compare Nike’s historical and projected EBITDA margin to the same peer group. Note how the company’s margin has remained fairly consistent over the last 10 years, ranging from 14.8% to 16.0%. This implies that Nike has generally relied on growing its top line in order to grow its bottom line.

Outside of Foot Locker, Nike boasts the highest EBITDA margins relative to its peers, which currently stands at 15.1%. Nike’ CEO Mark Parker recently accelerated the company’s manufacturing revolution initiative, which plans to reduce wasted material by using 3D printing. As a result, Wall Street forecasts margins to expand to 18.2% by 2021. This seems aggressive since Nike has never achieved EBITDA margins above 16%, so I capped them at 17.5% (still a figure the company has yet to reach) in the figure below.

Forecast Depreciation & Amortization Expenses

Depreciation and amortization (D&A) are usually embedded in cost of goods sold (COGS) or selling general and administrative expenses (SG&A) on the income statement. The model subtracts D&A to estimate NOPAT but eventually adds it back in the build-up to free cash flow because it’s a non-cash expense. Including it as an expense in the calculation of NOPAT allows the model to capture the tax benefits associated with D&A. While depreciation is a non-cash expense, the firm reduces its tax bill by expensing it, so the free cash flow available is increased by the tax savings.

Nike’s historical and forecasted D&A is shown in the charts below. I’ve kept D&A at 2% of revenues throughout the projection period, which is in line with its past performance.

Select a Pro Forma Tax Rate

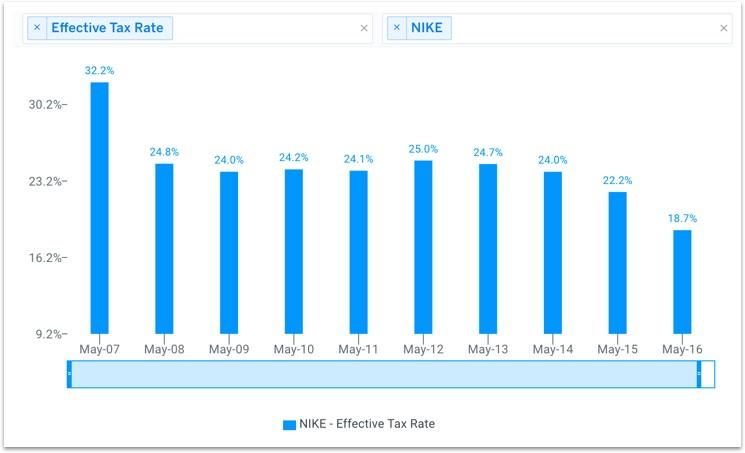

Companies are required to pay a portion of their profits to the governments in the countries in which they operate. A firm’s effective tax rate is calculated from the reported income statement by dividing taxes by operating income before taxes. The marginal tax rate is the rate owed on the company’s last dollar of taxable income. A company’s effective and marginal tax rate is not always the same due to accounting standards related to tax credits, tax deferrals and net operating losses (NOLs) carried forward. However, historical effective tax rates are useful for estimating a company’s marginal tax rate, which is what I use in the model.

Note that investors will want to keep an eye on whether the Trump administration lowers the United States’ marginal corporate tax rate in the coming months.

Nike along with many other companies report their effective tax rates in their quarterly and annual reports. Nike’s effective tax rate and my selected assumption of 23% are highlighted below.

Plan Capital Expenditures

Spending on plant, property, and equipment (PP&E), which is often referred to as capital expenditures, allows a firm to continue to operate as well as grow its operations. The amount of capital expenditures that Nike has spent (as a percentage of revenue) has steadily grown from 1.8% in fiscal year 2010 to 3.5% in 2016. Therefore, I’ve projected Nike’s capital expenditures as a percentage of revenue to continue its expansion by reaching 4.0% by 2019 and then to stay at that level after 2019 as shown in the second figure below.

Forecast Net Working Capital Investment

As a company grows, it typically needs to tie up more cash in working capital to manage its day-to-day operations effectively. The model accounts for the impact of this investment by first estimating Nike’s net working capital (NWC) as a percentage of revenue and then deducting year-over-year increases from free cash flow.

It is important to note that net working capital typically fluctuates more year over year than other DCF assumptions and is generally more difficult to project with as much confidence. Nike has historically required 14.4% of revenue on average for net working capital, but this figure has been as high as 18.7% and as low as 11.5%. The company’s latest fiscal-year NWC margin of 13.1% is in the ballpark, so I kept it at that level in the forecast shown in the figure below.

Notably, if I were to increase the assumption from 13.1% to the 14.4% average, there would be an additional $400 million cash outflow in the first projection year without much reasoning behind it. This is a mistake analysts will often make when projecting net working capital.

Calculate Free Cash Flow

With all required forecasts in place, the next step is to calculate projected free cash flow as shown below.

Step 2: Select a Discount Rate

The next step is to select a discount rate to calculate the present value of the forecasted free cash flows. I used finbox.io’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) model to help arrive at an estimate. Generally, a company’s assets are financed by either debt (debt is after tax in the formula) or equity. WACC is the average return expected by these capital providers, each weighted by respective usage. The WACC is the required return on the firm’s assets.

It’s important to note that the WACC is the appropriate discount rate to use because this analysis calculates the free cash flow available to Nike’s bondholders and common shareholders. On the other hand, the cost of equity would be the appropriate discount rate if we were calculating cash flows available only to Nike’s common shareholders (i.e., dividend discount model, equity DCF). This is commonly referred to as the difference between free cash flow to equity (FCFE) and free cash flow to the firm (FCFF). By using the WACC to discount FCFF, we are calculating total firm value. If we discounted FCFE at the required return on equity, we would end up with equity value of the firm. Equity value of the firm is simply total firm value minus the market value of debt.

I determined a reasonable WACC estimate for Nike to be between 8% and 9%. An updated cost of capital analysis for Nike using finbox.io’s real-time data can be viewed in your web browser. The DCF model then does the heavy lifting of calculating the discount factors by applying the mid-year convention as highlighted below.

Applying the discounting factors is done with multiplication. For example, to calculate the present value of the May 2021 projected cash flow, we multiply Nike’s cash flow estimate for that year of $4,418 million, by the matching discount factor (73.1% at the midpoint) giving you a present value of $3,228 million. The model follows the same process to compute the present value for each of the projected cash flows as shown below.

Step 3: Estimate a Terminal Value

Since it is not reasonable to expect that Nike will cease its operations at the end of the five-year forecast period, we must estimate the company’s continuing value, or terminal value. Terminal value is an important part of the DCF model because it accounts for the largest percentage of the calculated present value of the firm. If you were to exclude the terminal value, you would be excluding all the future cash flow past the horizon period. Using finbox.io, users can choose a five-year or 10-year horizon period to forecast future free cash flow.

The most generally accepted techniques to calculate a terminal value are by applying the Gordon growth approach, using an EBITDA exit multiple and using a revenue exit multiple. This analysis applies the Gordon growth formula:

As the formula suggests, we need to estimate a “perpetuity” growth rate at which we expect Nike’s free cash flows to grow forever. Most analysts suggest that a reasonable rate is typically between the historical inflation rate of 2% to 3% and the historical GDP growth rate of 4% to 5%.

As illustrated previously, Nike’s free cash flows are still growing at nearly 6% at the end of the projection period, so I’ve selected a slightly aggressive perpetuity growth rate of 4% (at the midpoint).

An EBITDA multiple is calculated by dividing enterprise value by EBITDA. Similarly, the terminal EBITDA multiple implied from a DCF analysis is calculated by dividing the terminal value ($107,741) by the terminal year’s projected EBITDA ($8,304).

Comparing the terminal EBITDA multiple implied from the selected growth rate to benchmark multiples can serve as a useful check. The 4% selected growth rate implies a terminal multiple of 13.0x (107,741 ÷ 8,304 = 13.0x), which is well below Nike’s current EBITDA multiple of 17.1x, but still above the benchmark and sector multiples. This seems reasonable because Nike’s 4% growth outlook at the end of the five-year projection period is considerably lower than its growth outlook today, which would warrant a lower multiple. Additionally, the company’s 4% future growth rate compares well to TJX Companies’ current five-year projected revenue CAGR but has superior EBITDA margins (below). Hence, I would argue that Nike’s implied 13.0x EBITDA multiple should still be above TJX Companies’ 11.4x multiple.

The terminal value calculated above is the value in the future as illustrated below. The discount factor in year five must then be applied to compute the present value. Then add the present value of the previously calculated future free cash flows and the present value of the terminal value to reach an enterprise value, as shown in the second figure below. Remember, the goal of the DCF model is to calculate future free cash flow and a terminal value, and then discount it to today to come up with an “intrinsic value.”

Step 4: Calculate the Equity Value

The enterprise value previously calculated is a measure of the company’s total value. An equity waterfall is a term often used by valuation firms, referring to the trickle-down process of computing a company’s equity value from its enterprise value. Note that in the event of a bankruptcy, debt holders will be paid in full before anything is distributed to common shareholders. Therefore, we must subtract debt and other financial obligations to determine a firm’s equity value. The general formula for calculating equity value is illustrated in the figure below.

The model uses the formula shown on the right to calculate equity value and divides the result by the shares outstanding to compute intrinsic value per share as shown at the bottom of the figure below.

The assumptions I used in the model imply an intrinsic value per share range of $48.68 to $67.70 for Nike.

Nike’s stock price currently trades at $53.45 (as of 1/25/17), 5.1% below the midpoint value of $56.19. Over the past 52 weeks, Nike’s stock price has reached a low of $49.01 and a high of $65.44. Interestingly, this 52- week range is right in line with the concluded intrinsic value range.

Final Notes

A DCF analysis can seem complex at first, but it’s worth adding to your investment analysis toolbox since it provides the clearest view of company value. I’ll end on this quote by renowned economist John Maynard Keynes:

— “It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.” —

Instead of focusing on the getting each of the assumptions exactly right, take Keynes’ advice on being roughly right. Select different assumptions deemed reasonable to get a sense for key drivers of value. Apply multiple scenarios (e.g., base case, downside case etc.) to get comfortable with the upside and downside potential of the company.

Get Started Now!

Note this is not a buy or sell recommendation on any company mentioned.